As you drive through Northwestern Wisconsin, you can see across the horizon for miles. If you drive with your windows down, you can smell a tinge of manure, the freshness of the air and, depending on your location, you can hear the hum of tractors, harvesting the season’s bounty.

If you’re looking for Barron, Wisconsin, you might miss it driving along Highway 8 toward the St. Croix Casino in Turtle Lake, past the sign referencing “Scandinavia” and antique shops. There and past, in less than 10 minutes. Big signs adorn the side of the highway, trumpeting “GOOD LUCK CHRIS KROEZE,” who is a finalist on this season of NBC’s The Voice. You will see the Jennie-O turkey plant topped by an American Flag casting its shadow, beckoning to job searchers with an advertisement featuring a Somali woman in red Hijab underneath a factory hard hat. “Start a new job, begin a new life,” it urges. What you may not see are the two small black-and-white signs, “Find Jayme Closs,” “Bring Jayme Home.” What you will not miss, is the yellow caution tape, the FBI SUVs, and the countless news vans rolling around town, hoping to see something a camera can’t miss.

Barron, Wisconsin, population 3,318, a formerly homogenous largely white and Christian town which grew out of a logging camp in the 1860s before turkey became the dominant industry, was already one of the most interesting communities in the state even before CNN paid attention. It exists as a microcosm of a changing America.

“This is the way the world is going to look in 20 years; like Barron,” Barron School Board member Dan McNeil says. Privy to the changes the town faces, McNeil has been an active town member for many years. “It’s not going to be what color you are or religion you are, it’s who you are and how you treat other people.”

The weekend before Halloween, a gruesome murder mystery and child abduction catapulted the small, complex, Wisconsin town into the national spotlight, unmissable, as every cell phone in the state received an Amber Alert on Monday, October 15, 2018 for the missing girl, 13-year-old Jayme Closs. Her parents, who both worked at Jennie-O, were shot to death in the family’s rural home right outside Barron, and Jayme was, simply, inexplicably, gone. Even the police openly admit they have no leads.

Barron residents in the search for Jayme Closs dressed in camouflage sweatshirts, blue jeans, Harley Davidson hats, work boots and yellow vests as they took to the shoulder of Highway 8. But down the road a different story about this already complex town came into view; at a children’s soccer game, little girls ran around in Hijabs yelling to their teammates in Somali. Except for the Mosque Al-Rahma and a Somalian restaurant, a passerby might never know that at least 13 percent of Barron’s population is now black. The diversity is almost entirely from immigrants and their families who are Somali and Muslim. Barron is a pocket of rich ethnic and religious diversity in a rural, largely non-diverse county in a largely non-diverse state, especially up north. It’s also an area that has political currency; both the county and city flipped from Barack Obama in 2008 to Donald Trump in 2016.

What was at first almost invisible comes slowly into view, however, the more time one spends in town. Today, a woman wearing traditional Muslim dress, called an Abaya, travels down the leaf-strewn and American flag festooned Main Street, which in this quintessential Middle American small town is called La Salle Avenue. You might be welcomed into a hidden Somali male-only tea room for piping hot Samosas. La Salle Street is where you will spot a sign for English classes pasted on a window, it’s where you can purchase camel’s milk and goat meat spaghetti (pasta is a staple in Somali cuisine because the country used to be an Italian colony), and it’s where a Somali woman in a black Abaya walks near young Caucasian men in camouflage who careen around on ATVs.

A sign for the Barron Business District lists “Islamic Center,” next to “Churches: Lutheran, Methodist, Catholic.” A second mosque is just off La Salle, and it’s more weathered than the first, green painted paneling with the spine of metal where an awning once was. It’s next door to a shop that sells Somali clothing in vibrant colors and fabrics.

The high school has English as a Second Language classes, and most of the students in them left Africa when they were young, many living in crowded refugee camps in Kenya with poor educations and living conditions. All of the students were from Somalia, fleeing for safety and security as the civil war rages on in their homeland.

“Home is Africa,” one of the boys in the ESL class says. “We’re safe here,” one student insists.

This town in the national spotlight, still so segregated in ways, has found some unity through the children, both the one who is missing and the ones who aren’t. A soccer team has helped unite students of all ethnic backgrounds.

But right now it’s the student who is gone occupying people’s concerns.

Only a few miles from the high school, over 300 volunteers, exceeding the sheriff’s request of 100 people, line up to sweep the 14-mile stretch of road from Barron to Turtle Lake looking for clues leading to Jayme Closs, a Caucasian teen. In the Somali restaurant, its owner puts out reward posters for the missing child.

The complexity of the town unraveled before the eyes of anyone who took the time to look beyond Highway 8, and into the true composition of this small Wisconsin town, for the first time, on the radar of millions.

“In America, if you don’t become part of the community you suffer a lot,” says Kaltuma Hassan, the owner of the Amin Restaurant, which doubles as a store for the Somali community. She moved to Barron in 2015 from South Africa, where she was a businesswoman after fleeing Somalia.

“A community is a friend, it is everything to you,” Hassan says. “A community is important. It is very, very important. It is where you share happiness or badness.”

She stands in front of a wall with a disheveled collage of various beauty and healthcare products available for purchase. The store is like a mini-mart selling everything from rice to “Facebook” cologne. Mass-produced goods lined shelves, and Somali goods were baked and wrapped in saran wrap, such as sesame cookies, to be presumed as homemade delicassens.

Henna crème and candles sit behind the front glass counter where DurDur Bakery and Miswak wafer desserts are perched on top. On the counter are two tip jars: one ripped on the corner and secured with Scotch tape and the words “Al-Rahma Mosque” in typed font; the other is handwritten with Sharpie with the words “Al-Toqwa Mosque.” Past the counter, stands an area with tall shelves stacked with rice, spices, and other ingredients that make up the only Somali grocery store in the entire town.

“Barron is our home,” Hassan says.

Immigration Stories

Wisconsin became the 30th state on May 29, 1848. Before European settlers came to Wisconsin in the 19th and 20th centuries, the land was largely home to Native American groups including the Ioway, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Ojibwa, Sauk and Potawatomi. René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, or Robert de La Salle, a French explorer, explored the Great Lakes and Canada, forcibly introducing the first diversity to the region, foreshadowing the great change in demographics since then. For more than a century afterwards, though, the area was largely white, with the Native peoples consigned to a nearby reservation.

Barron did see Hispanic migrants earlier on, but they shared a religious link with the largely Scandinavian and German inhabitants: They were Catholic and Christian, whereas most of the Somali people are Muslim.

“Welcome to Barron,” says a painted mural on the side of a building that contains a Christian church, dairy farm, and forests. Other signs have turkey feathers.

At 83, John Mayala is a man of few words and many seasons, who remembers being a 12-year-old boy on his parents’ farm when Wallace Jerome, the founder of Barron’s Jennie-O Turkey factory, rolled into town.

“The guy had turkey eggs and was driving a ’41 Pontiac,” he said, smiling. Now the plant, owned by Hormel, is the dominant industry.

Like many northern Wisconsin communities, Barron County is 95.5 percent white, according to Census data. Most Caucasian people in the state have German ancestry, with Irish, Polish and Norwegians rounding out the heritage. In the past, Wisconsin has attracted immigrants, mostly from western Europe. More recently, waves of other groups came to the state, such as the Hmong and immigrants from Mexico.

A 2013 study by The University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh found that Wisconsin was less diverse than 38 other states. That’s even truer of northern Wisconsin, as almost half of the minority population of Wisconsin lives in one county down to the Southeast: Milwaukee.

The U.S. Census Bureau says that 87.3 percent of the state’s population was “white alone” in 2017.

Black or African-Americans accounted for 6.7 percent of the state’s population, the Census Bureau said. Only 8.7 percent of Wisconsin’s population spoke a language other than English at home, according to The Census Bureau.

Now contrast that with Barron. La Salle Avenue is likely one of the more diverse streets in northern Wisconsin. According to Heritage Somali and Identity in Rural Wisconsin, an article in Journal of Language Context, by Joshua R. Brown and Benjamin Bennett-Carpenter, more than 70,000 refugees have settled in Wisconsin, with 79 percent Hmong.

The article describes Somalis as “one of Wisconsin’s newest refugee groups” and says they are “racially, religiously, and linguistically different from the demographics of the Wisconsinite majority, e.g., white, Christian, monolingual Anglophones.” Some Somalis hold temporary residency because they hope to return to Somalia some day, says the article.

The article adds that most Somalis are “Sunni Muslim and Islamic practices inform much of Somali culture including dress, food, ritual, gender roles.” Somalis became refugees when the country fell into civil war, according to the article. Americans and especially veterans remember the 18 American soldiers murdered in Mogadishu and captured in the movie Black Hawk Down.

According to the article, many Somalis sought refuge in Minnesota communities, especially those with plants where they could find jobs that did not require English.

“Waves of Somalis have come to rural Barron, Wisconsin,” says the article, fleeing crime in the Twin Cities, seeking new jobs, and lured by a “high school graduation requirement that does not require an English language essay test.” Somalia, a country on the eastern coast of the Horn of Africa, was home to over 10 million people before civil war broke out in 1991. Thousands of Somalis were killed by war and famine, and millions more fled to neighboring African nations. In 1992, Operation Restore Hope – a collection of 24 nations offering humanitarian aid – allowed Somali refugees, living in Somalia or in refugee camps, to come to the United States for asylum.

The Somali people began immigrating to Northern Wisconsin and Minnesota in the mid-1990s in a search for a better life, with more freedoms and opportunities.

“Somalia is war; people flee into the neighboring country. Before we left, we had a business, a farm. Now in Somalia, they kill a lot of people too. They don’t care who you are. Back home, we are the victims,” says Jafar Hirmog, a Somali man living in Barron, who works at the grocery store.

“I miss it a lot. The culture, where you were born—you know everybody. Most [people] are welcoming. We find work here, connect with each other, learn culture, learn people, go to work. We keep much [of our culture] – that’s the only way to be Somali.”

Religion is very important. “[Praying] is like exercise. Really every angle, everything works perfectly,” Hirmog says. Touching his forearms and pointing to his knees, he repeats, “It’s like exercise.”

Within the town of Barron, Wis., a secondary population exists, and with them, a whole social and cultural identity, far different than those who exist outside of their close-knit community.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, from 2002-2016, Somalians represented the third highest refugee group in Wisconsin, after Myanmar and Laos. Barron was the 14th highest community in refugee resettlement, behind larger cities like Milwaukee, Oshkosh, Madison and Green Bay. One hour west of Barron, Minnesota is estimated to be home to around 80,000 Somalis.

The U.S. Census Bureau’s Community Survey says that, in 2017, blacks were 13.4 percent of the City of Barron’s population, 447 of a total population of 3,346. That’s up from the last full census in 2010, when the city had 301 black residents, or 8.8 percent. Some local news sites put the Somali population today as almost double that.

There is also an Amish store in town and a Chinese restaurant, and it’s possibly to run into people in the area who speak only Spanish (two young men in a nearby tavern were using a gadget to translate. The census lists 132 people of Mexican descent in Barron and no people of other ethnic backgrounds than white, black or Hispanic).

What may seem like an interesting social experiment, transplanting hundreds of African Muslims in the middle of white, Christian, rural America, started in a series of culture clashes. Fights broke out in schools, openly rude and intolerant townspeople existed and Somalis were living in a separate quarter of town, minimizing interaction. Those are among the most prevalent indications of a town in conflict. Despite this, the Somalis are here to stay; returning to a lawless, violent country where devastation and fighting is constant among rival warlords and Islamic insurgents, is not an option.

Citizenship Hopes

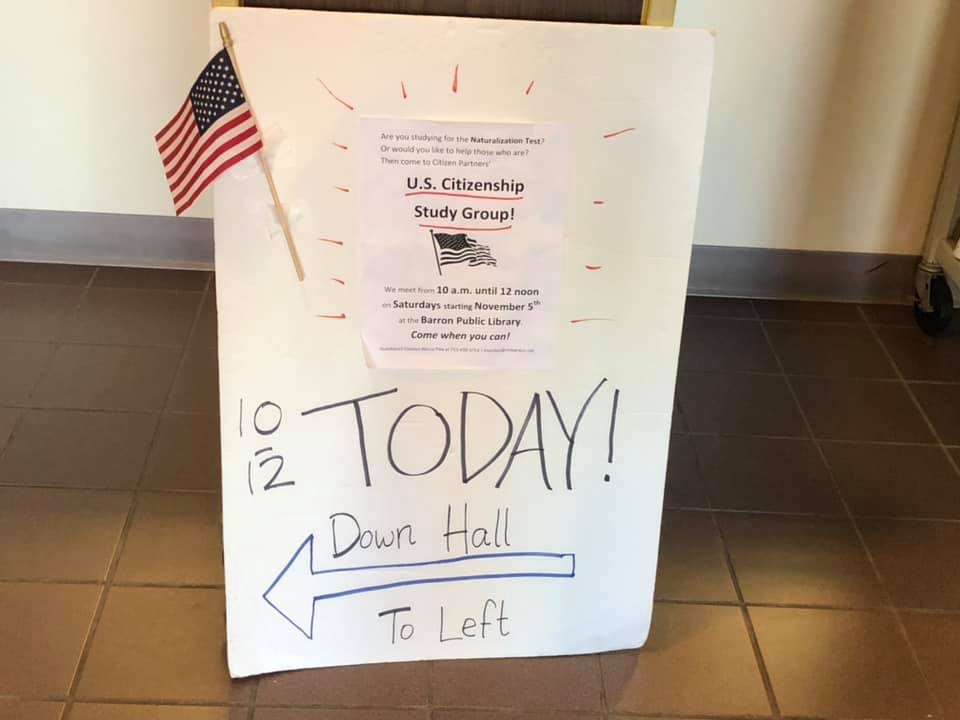

With hopes of staying in rural America, many Somalis are working to gain citizenship. At the Barron Public Library, there is a large handwritten sign with a little American flag stuck on it. “U.S. Citizenship Study Group!” it blares. “TODAY! Down Hall To Left.” Inside the room, Somali people study American government and learn the names of Wisconsin politicians like Ron Johnson and Scott Walker. “Rights, good things you want,” says a sign drawn in marker on a table. It lists things like “freedom, press, assembly, speech, religious, liberty, life.” They study under a large American flag that stands under a sign on the wall declaring “Barron American Legion.” Somali children in brightly colored pink down jackets color at a table nearby.

One recent Saturday morning, three Somali men sit in the citizenship class. The class was held in a well-sized room in the library. It has photos of prominent political figures like U.S. Senators Tammy Baldwin and Ron Johnson on posters, explanations of the differences between the state and federal governments, white floors with no carpeting and square tables that are scattered sporadically throughout the room.

At some tables, Somali people were writing sentences like “The President of the United States is Donald Trump.” (It turns out that the Somali community is not monolithic politically; some Somalis profess to vote for Democrats, but others said they were fans of Trump, although some were angry about the travel ban.) Somalis and locals sat together laughing, talking and studying.

The woman running the citizenship class fell into tears as she began to explain how badly she wanted to help the Somali people. She shared that she believes that everyone deserves an equal chance and wants to make sure that the minorities in her community are secure and capable of obtaining citizenship.

Nancy Pike is a member of a local community group named Citizen Partners. She, along with others in the group, volunteer at the Barron Public Library once a week to help Somali refugees succeed on their U.S. Citizenship test.

The citizenship test is a 100-question civics test with an added component of reading and vocabulary. It is a requirement of the U.S. Government that any immigrant or refugee wishing to become a citizen must pass the exam. This is not easy to do when English is not your first language.

“The number one issue so close to my heart and always on my mind is all the families here in Barron who have family members stuck in Africa indefinitely,” said Pike.

Warsme, Abdi and Daud have lived in Barron, Wisconsin for six years and were studying for their citizenship test with hopes of becoming legal American citizens among their peers.

The men shared that the cost for the test was $725. “Most people are nice; a lot of people very good,” said Abdi, when asked what it’s like to live in Barron. “Out of 100 percent maybe 5 percent are not nice. We working together, helping together, a lot of people are very good; we don’t want problems here,” added Warsme.

Warsme said he sends between $800 and $1,000 back to Somalia every month, for his family. Like many immigrants, Somalis aren’t afraid to do the tough work, slicing turkeys at the Jennie-O Turkey Plant run by Hormel, alongside locals.

The three men all worked at the Jennie-O factory and work full shifts, rotating between first, second and sanitation shifts. Warsme said that many weeks he has worked 70 hours.

“Sometimes 65 hours of work, or 35, 40,” said Abdi. “I like my job.”

Cultural Identity

Hidden even further within the composition of the town, a small “tea room” is tucked away in plain sight behind a non-descript storefront on La Salle Avenue, and, after the citizenship class, a small group of student journalists is invited there. It’s a private space for Somali men to gather, converse, play board games and watch soccer around a threadbare wooden table. The men here were hospitable, offering piping hot sweet tea. It was aromatic, and the men refused to accept payment for the beverage. However, they also don’t generally allow women into the space due to religious preference.

Dean Freimund, who was helping Somali immigrants at the citizenship class, leads the students to the tea room. He, like a Somali man named Isaak Mohamed and like Pike, are the cultural bridges who help create sinew between what, in some ways, remain different communities. Everyone seems to know Isaak. And many people seem to know Dean.

Afternoon tea in Somali culture is called asariya.

The men offer their visitors Samosas, which are deep fried triangular shaped pastries stuffed with spicy meat.

A heavier set gentlemen wearing a gray shirt and blue jeans, with glasses hanging from his face, Freimund was born in Plymouth, Wisconsin. He felt the call in his life to be a Christian minister when he was 20-years-old. He spent the next 20 years of his life in ministry before leaving Plymouth and settling in Barron. When the Somalis began to arrive, he didn’t think it was accident.

“I believe God bought the Somali here; he hates vanilla ice cream every day of the week,” Freimund said, referring to the majority white population in Barron. “Without the Somali here, Barron would be boring.”

In the Somali tea room, which is tucked away on La Salle Avenue behind a nondescript awning that mentions financial services and coffee, Dean and several Somali men warmly greet each other like old friends before settling in around a scuffed wooden table to eat Samosas and watch soccer on the television set.

“If Jesus Christ drove his Pontiac through Barron, if he had to stop anywhere, he would come to the Somali tea room,” Freimund says, and it’s a friendly place, where food is freely offered and camaraderie evident. However, Freimund warns that women are not usually accepted in the tea room due to religious beliefs and suggests that a female reporter stand off to the back. Eventually, though, Somali men welcome the reporter into the main area. One Somali man in the tea room smiles broadly and declares that Barron is “Mogadishu.”

The Somalis maintain their cultural identity, and often their traditional dress and language, and for this, they stand out in a farming area where signs proclaim that “Country gals” support Chris Kroeze, the phenom from Barron who is a finalist on The Voice.

Men and women dressed in abayas, hijabs and colorful clothing can be seen walking the streets within Barron. Many of the Somalis live together in a single apartment complex. Somali men don’t always acknowledge women’s greetings on the street, which confused non-Somali residents at first. Despite the proximity to city center, driving up to the Somali Apartments – where most Somalis in Barron live – is like entering a different city. Stepping out of the car, into the parking lot of a run-down apartment building with tattered screens, an abandoned mattress decorating the front lawn, tinged by the stress of inhabitants moving in and moving out, it was hard not to notice the ethnic smell of food seeping through the crevices around doorways.

Tom Kite, the manager of the building, called out the language barrier as the root cause for why Somalis are not fully integrated within the community.

“There was tremendous tension,” said Kite. “For many white people here, this was the first time they’d ever seen a black person.”

Some had, in fact, never seen a black person, or a Muslim person. Coworkers at the Jennie-O Factory pointed out the intermittent breaks the Somalis would take for religious purposes. Others acted as if they hadn’t noticed the Somali people even lived in the town.

The Heritage Somalia and Identity article says the Jennie-O plant that drew them used to be largely Latino in workforce. According to the article, Barron’s Somali population grew by 722% from 1990 through 2010 to 400 people.

The Somali people openly addressed the biases.

“[We have] respect for religion,” shares Hirmog. “But everything is political. The terrorist guy, they become the Muslim image. In the Muslim way, if you kill one person, you kill the whole human world. [Terrorists] claim to be Islam, but they are not really.”

Hirmog began sharing stories of life in Somalia and said that everything he expected in America came from American movies. Coming to the country after spending time in a Kenyan refugee camp, this was his best opportunity at a better life. He asked that his photo not be taken and became nervous after the prospect was suggested.

A Report of the Wisconsin Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 2017 discussed hate crimes in Wisconsin and said that Wisconsin’s minority populations face disproportionate social ills, such as poverty. Some anti-Muslim incidents were reported throughout the state.

In 2012, the U.S. Government released a report called “The Somali Community in Barron, Wisconsin, and the American Dream.”

The report describes how Somali people have had to navigate European influence historically through colonialism, gaining independence “from Italian and British rule in 1960.” Somalia was formed out of six major clan families, that often conflicted with each other. Hundreds of thousands of Somalis were “killed in the war or from the famine.”

Somali people were drawn to the Minneapolis-St.Paul area, which became the “de facto Somali ‘capital’ of North America with between 10,000 and 30,000 Somalis residing there,” said the report, adding that they were drawn by jobs and “experienced refugee social service agencies” that had helped settle the Hmong.

Issues in Barron in the early days included a lack of interpreters, no halal meats in the grocery stores, and conflict at school over girls wearing the hijab when non-Muslim students were not allowed to wear hats, the report explains. Tensions grew after 9/11 when a “Somali flag was desecrated.” The Somalis were clustered in an apartment complex on the town’s edges, then as in now.

However, the report outlines the changes the town made, from the ESL program in the school district to the soccer team that “helped bridge cultural gaps.”

Other small towns also found Somali refuges amidst their populations, including “a vegetable canning plant in Balsam Lake, a computer manufacturing plant in Chippewa Falls, and a furniture plant in Cumberland.”

Adbi Kusow, a professor of Sociology at Iowa State University told the committee that the Somalis “have experienced a spontaneous civil war without any warning.”

He discussed how the Somalis seemed to “spontaneously appear” in towns like Barron.

“The Somali society may be one of the few societies in the United States that is African, black, Muslim, and non-English speaking at the same time.”

Forging Community

Throughout Barron, Somalis own businesses to cater to the needs of their community.

Down the street, Fadumo Hassan tidied up and smiled as the door to her store, Bushra Fashion Shop, swung open, welcoming customers. The walls were lined with patterned scarves and clothing, and aisles were narrow as the floors and shelves were covered in miscellaneous clothing and beauty items. She began showcasing the perfumes lined along the back wall, carefully taking droppers out of each glass bottle and sharing the smell, and she smiled back as her products were affirmed through the polite nods and smiles.

Carefully, Fadumo dripped one of her favorite scents on the reporters’ wrists. The liquid seeped into the skin and, as it did, she smiled. In this moment, she seemed to be sharing more than the musty, floral oils. At mention of the mosques, she began to show headscarves, each one more beautiful the next.

Together, coming to a conclusion on the best scarf, Fadumo demonstrated to the student journalist how to wear the scarf, carefully placing the silk on the head, and wrapping it carefully around the face before placing excess fabric behind the shoulders.

“It is your color,” Fadumo said through a smile.

In the mosque, Isaak Mohamed, who is a community leader turned to by Somalis and non-Somalis alike, explained that it was important that everyone who came to pray washed up before doing so, an action that wasn’t as simple or tedious as washing your hands after using the restroom.

Instead, the movements seemed to carry a sort of weight, a religious ritual, sacred to the Somali people and the Muslim religion. Mohamed splashed his face with water and scrubbed with the entirety of his palms, making certain to clean every inch of his face, including his ears. His motions were mechanical, something memorized and specific, and it was a clear he had washed this way hundreds, maybe thousands, of times.

Barron Unvarnished

The fact that Barron has become a national news story is, like the area’s unique diversity, not immediately evident when you drive into town. Aside from the Sheriff’s Department, one of the only other places in Barron that was advertising the search for Jayme Closs was the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). A sign in front of the white, nondescript building read “FIND JAYME CLOSS” in black letters, above information about “WHISKEY & TOPAZ” from 8 to 12 p.m. on October 20. Around 1 p.m., the bartender is only accompanied by a few white patrons.

In a town this size, it seems as though the dividing line of segregation and misinformation was all the more prevalent.

Here, the views are less integrative and more combative.

“We don’t want them here, but they came, and we take care of them,” says Elaine Johnson, a regular at the VFW, of the Somali people. She sits at the end of the bar drinking a Diet Coke through a straw.

She called the apartment where many of the Somali people live in Barron, “Somaliville.”

Elaine had nothing but positive things to say about the Somali children, but a man who wished to remain anonymous was sitting two stools down from Elaine and interjected. “They’re just like any population, really,” he said. “A lot of people don’t realize what they had to go through to come here.”

According to Johnson, racial and cultural division thrive in Barron because people refuse to get to know one another. Although she has eaten at the Somali restaurant downtown, she scrunched her nose thinking about the Somali men and what she described as their lack of hygiene, commenting on supposed poor habits when it comes to “washing their genitals.”

Several miles down the road, just across the county line into Polk County, sits another bar, this one called Straight 8. A handful of battered vehicles park outside the long, burgundy building with a large Packer helmet pinned to the siding. A few people sit at the bar for cheap drinks, only $3.50 for a double tall vodka soda in a small, clear Solo cup, or $.50 for homemade Jell-O shots. Men with black, oil-stained cuticles ran fingers around the small containers before dumping the dessert-like libation into their mouths.

Others try their luck on the slot machines pressed up against a faux wooden wall, underneath neon signs, some sit and watch football on the televisions, and a couple men shoot pool, murmuring under their breath at the other as they become engrossed in conversation or baseball highlights, preventing them from taking their turn. Cigarette smoke fills the room clinging to the hair and embedding itself in the clothing of all in attendance, because according to the patrons, it’s cheaper for the owner to pay the smoking fine than it is to kick the smokers out.

Here men talk after a long work day, about everything, from their day at work, to their Tinder dates and most commonly, what the next drink would be, though most knew the answer—the drinks weren’t changing from Miller on draught. The men in the bar were stocky, with the exception of the few, and all indicated having worked in a job that was physically demanding. With reporters from Milwaukee sticking out like a sore thumb, it took several attempts to start a conversation, and when it started, the anger quickly burst forth.

The men were Caucasian and, in one case, half Native American. They proclaimed themselves to be Trump supporters who like the president’s stance on guns and because they don’t see him as a typical politician. (One Trump loving man shooting pool with arms littered with tattoos declares he can’t vote, though, because he’s a “federal felon” and former meth dealer.)

They expressed great hatred for the Somalis and made comments about them that feel cruel to repeat, although they struggled to explain why beyond claiming that the Somalis depress wages and take their jobs. These men are car mechanics and multi-generational farmers, they work multiple jobs to barely get by, and, one, at age 29, was a first-time voter – for Trump. They don’t all have TV sets, they like guns because they use them to shoot coyotes that imperil their cows, and one had a scar on his neck from a baby bear that fell out of a tree and gnawed away at him. They laughed about an animal rights activist from Michigan who they say follows them around the woods when they hunt, shooting video.

They said the Somalis should “just leave” and should “get out.” Locals confide that people avoid buying houses in Barron now because it’s become the wrong side of the tracks.

“They need to get the hell out of here,” says one of the men, Travis Peterson, of the Somalis. He’s the farmer with the bear scar. “This just doesn’t happen here. Down in Milwaukee and Chicago, you see it all the time. They’ve wrecked the town of Barron bad.”

However, down the road back in Barron, the narrative gets more complicated when some of the Somalis reveal proudly that they are also Trump fans. “I think he is a straight guy,” Hirmog, the Somali man working at the grocery store, says. “He keeps his word.”

The political overlay also gives the tiny town national currency: It’s in a County that flipped from President Obama to Donald Trump. It’s tempting to ascribe this to the refugee influx, except that dates to 1995 and Obama won here after that point. And when you talk to the Somalis about politics, you find a mixed bag, with Isaak Mohamed and other leaders saying they vote Democratic, but some of the Somalis themselves revealing they support Trump.

Trump won Barron County handily, earning 13,606 votes to 7,879 for Hillary Clinton, according to Barron County spreadsheets. He won the City of Barron vote too. This was a pattern repeated enough throughout rural, working class areas of Wisconsin (and states like Pennsylvania and Michigan) to give Trump the White House. The area was growing more conservative by 2012; the city went for Barack Obama but the County slightly for Republican Mitt Romney. In 2008, Obama won the city and the county.

Despite being unable to vote yet, Hirmog, the Somali man working at the grocery store, supports what he perceives as a cultural consistency with the Trump administration.

“Trump does not like the gay people, so [we] like Trump for his cultural way. In the ’90s, people thought if you touch people with AIDS, you get it like that,” he says bluntly, snapping his fingers.

This is Barron unvarnished.

His eyes grow wistful as he says, “It’s like a movie when you are outside [the country] and you hear about America. Somalia is war. Back home, we are the victims. Here you have rights: to have a lawyer, to go to court.”

Gerry Lisi, Chairperson of the Barron Democratic Party, says the Somalis are very socially conservative and believes Republicans would get along with the Somali immigrants if they could simply get past the differences of their outward appearance.

“It is surprising to me that the Barron County Republican Party has not established a close and mutually beneficial relationship with a community of people that encourages strong, large two-parent families; insists on weekly church attendance; discourages drinking and smoking; and holds conservative views on homosexuality and abortion. So much for Republican family values,” said Lisi. “We Democrats are glad to ally ourselves with these fine folks and enjoy seeing them establish families here.” The Republican Party of Barron did not return calls seeking comment.

Mayala, the elderly man who remembers the turkey company starting, voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016. Why?

“Republicans never helped the working man any,” he says with a half-grin.

Barron County Supervisor Roberta Mosentine doesn’t have positive things to say about the Somali immigration. Mosentine is known by some for unfavorable views of the Somalis in Barron and this was shown right in the beginning of the interview.

“They arrived seven years ago and created a lot of shock amongst the Barron community,” she reveals.

She began to speak about numerous reasons why she believes the Somalis were not great neighbors to the community. Mosentine claimed their religion is just too confusing, the level of cleanliness is low, and she is not a fan of their food, churches, and work atmosphere. Those who are not Somalis cannot enter the Somalis cafés or other businesses, she insisted.

“They pray a lot, even at work, and a lot of people do not like it,” she says. “Men say hi, but the women say nothing.”

Coming Together

According to Barron School Board member Dan McNeil, there was the most intense conflict when the Somali migrants first arrived in town. Culture and language barriers kept the communities apart. Although there are clearly still some remnants of that, in other ways, connections are being formed, and Barron is slowly unifying.

The biggest strides toward inclusiveness are made in Barron area schools.

The Barron Area School District consists of Barron High School, Riverview Middle School, Woodland, Ridgeland-Dallas, and Almena Elementary Schools. The district instructs over 1,000 students in grades PK through 12. Surprisingly, the district did not have a soccer program at the youth or high school level until former Superintendent Monti Hallberg was driving past a field where four Somali teens were kicking a ball around.

“I parked my car and got out to watch for about five minutes and I could tell, this was their sport,” Hallberg said. That ignited an idea that grew: Hallberg believes the key to unity was through the children, and it could come about on the soccer field. He’s now the superintendent of the American International School in Saudi Arabia.

Today there are over 400 youth involved in Barron soccer programs, which has become a bridge for white and Somali students to come together. Now those students high-five in the hallway and sit together during lunch.

At the high school, next to a recently-installed prayer room, a white instructor who knows very little Arabic teaches Somali students in an ESL classroom. They sit in two rows facing the whiteboard. Girls adorned by colorful head scarves sit together, laughing often and yelling at the boys to pay attention.

One student, Muhammad, is one of the students who’s most integrated into the mainstream high school. He was able to learn English before he came to the United States. After being in the ESL classes for only a short amount of time, he was placed into the mainstream classes where he has a lot of friends, some still in the ESL classrooms, like his brother, and others who have never stepped foot in that wing of the school.

As the youth of Barron are becoming more integrated, this has created cultural issues at home. The elementary school children are speaking English earlier in their lives, often becoming fluent in it instead of their “home language.”

In Islam, praying five times a day is required. During the school day, there are two prayer times that fall during the day. The Barron High School decided to embrace the religion of the students and turned an old storage area into a prayer room for the students.

Located next to the ESL classrooms, the students are able to leave class during prayer times to pray. A divider in the middle separates the boys from the girls, a practice in the religion.

The classrooms provided a place for this common ground. As students talked about moving out of the ESL classes, they would shake their heads and laugh that they weren’t going to leave ESL.

“ESL forever.” The students said it as they laughed with each other, sharing comments among themselves in both Arabic and English.

There are other people, both Somali and non-Somali, working to make things better. Marsha Iverson-Smith moved from Rice Lake to Barron in the 2000s and now helps Somalis with literacy and adult basic education. She also helps with obtaining driver licenses and GEDs. A former student of hers, Farhiya, whom she describes as super dedicated and hardworking, has passed and completed her citizenship.

She says that a lot of Somalis come to Barron because it is small and job security is high. The turkey factory is always hiring Somalis and refugees.

She works hand-in-hand with the refugee services coordinator Nasra (she asked that her last name not be printed).

Nasra invited a student journalist to eat with her and her family for dinner. They served Pasta with Suugo. According to Xawaash.com, traditional Somali pasta sauce used beef cubes to make the meal last longer because of “home economics” and making pasta sauce was “an every day affair.”

She was one of the first Somali residents in Barron. Nasra explained that she came to Barron as a refugee in the 1990s through the International Organization Migration program from Somalia. She came to the United States with the help of her brother. She lived on government support for a few years and ended up in a couple of states before she moved to Barron in 1997. She had a friend in Barron who insisted she should come work at the turkey factory.

At first, she didn’t plan on staying long in Barron. She was one of the very few who migrated to Barron, and the biggest hurdle of all for Nasra was “finding a place to stay.” She said that those living in Barron “didn’t understand them” at first, but English helped her get through a lot, and she not only was able to find a place but get a car. After a year or two working, they promoted her to become a translator for Turkey Jennie-O, and she stayed there another five years as the interpreter. Many Somalis were migrating to Barron around that time and there was no translator but her.

She remains in the role of community liaison today. She was promoted to working at the workforce resource center where she currently works. She helps incoming refugees with finding employment, housing and other resources. Today, new Somali arrivals to Barron find a network of people like Nasra ready to help them.

Mystery Unsolved

On a crisp October day, the community gathered in a field just off Highway 8 to organize a search for the missing girl, Jayme Closs. The sheriff’s press conferences are noteworthy for the lack of clues he has released about motive or suspect. He stresses that he simply doesn’t know why this happened. The girl’s parents, who worked at the turkey factory, were shot, and the teen simply gone. Other than the meth problem, violent crime is not common in Barron.

Barron, this deeply intriguing town with a complex identity, suddenly thrust into the national spotlight by intense media coverage of a brutal murder and kidnapping mystery, unites through its children.

Down the road a few miles from the Somali apartment complex, the FBI and sheriff’s department have erected a command post outside the Closs home and volunteers in bright emergency vests comb the ditches for evidence they never find but do unearth a meth needle (the area is also one of Wisconsin’s worst meth regions).

As volunteers scoured both sides of the 14-mile stretch of road between Barron and neighboring Turtle Lake, where there is an Indian casino, they swatted reporters away like flies trying to land for a moment on a town in disarray.

Although there were no colorful hijabs or abayas in the sea of neon yellow vests in the search for Closs, people in the Somali community are also coming together to support the effort.

Kaltuma Hassan, the restaurant owner, left Somalia when she was 11-years-old. She worked as a businesswoman in South Africa for nine years before coming to the United States. She and her husband have seven children, five of whom are still in Somalia. Despite the incompleteness of her family, Kaltuma considers Barron to be their home.

A cliched scene of palm trees is painted on the powder-blue walls, and you can find exotic spices like cardamom on the shelves (according to the St. Paul magazine, that’s one thing that Scandinavians and Somalis share in common: Cardamom.) Although they differ in religion and skin color and language and custom and dress, the Somali and non-Somali residents of Barron share a desire to simply make a life for oneself and one’s family in America. They share the cliched “American dream.” They build businesses, and they seek to better themselves, and they seek sustenance, and they want safety. In all of these ways, they unite.

“It’s a community,” Hassan repeats, returning to the theme she has emphasized several times.

“When I care about you, you care about me. Your children are my children.”

This overview story was written by Madison Sepanik and Sloan Sullivan with some writing and reporting from student journalists Tess Klein, Aubry Bowen, Talis Shelbourne, Darien Yeager, Hailey McLaughlin, and Michael Jung.